Cup o' Sugar

Giving rather than taking, and knowledge-making

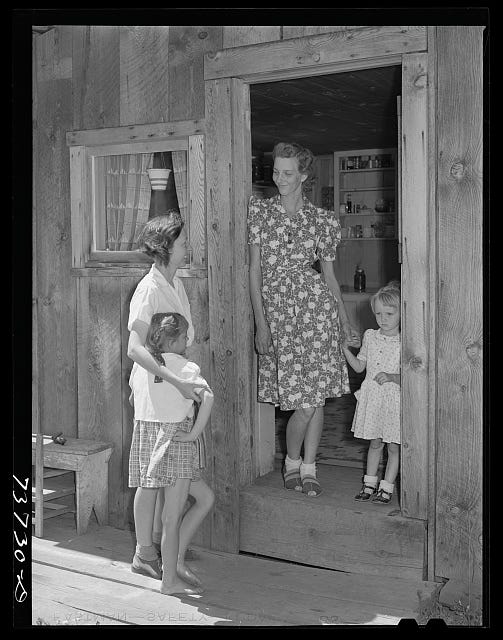

Years ago while I was living in New York, I had a million-dollar idea, one of the many great ideas I’ve had between dispiriting moments of regular employment. I wanted to develop a mobile app where you could source ingredients from your neighbors, and share ingredients in turn. I initially wanted to call it “Spice Grindr,” but after some spirited conversations with friends about infringement, renamed my proposed concept as “Cup o’ Sugar.” Not only did I think it could work (and prove viable if you could get advertisers, especially from food retailers), especially in places with tons of culinary diversity within each apartment building, but I thought it could be a means of community connection. Especially when I was editing cookbooks and testing recipes during my day job, I found countless instances when, after a rewarding trip to Kalustyan’s or Great Wall to find millet or asafoetida, I’d use a single teaspoon for the recipe and leave the rest to languish in the pantry for months on end. What a resource it would be to broadcast my available pantry items to a 30-block radius, to make trades for a few ounces of red vermouth or a cup of flaxseed when needed! How nice it could be to spread the bounty of my CSA around, especially on those weeks where I was swimming in kohlrabi or rutabaga! What a wonder it would be to find other home cooks to connect with, to ask what they were cooking, to create a bond of mutual appreciation in our shared moment of need. I liked the notion of my home kitchen as a resource, far beyond the needs of my own household.

In the late nineteenth century, the anthropologist Franz Boas wrote about the principle of potlatch among Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, a particular kind of gift-exchange that facilitated the creation of political, social, and cultural bonds. Boas noticed that, especially at significant community events such as weddings, coming-of-age, and death rituals, members of the Kwakiutl Nation would exchange property, objects, or foodstuffs with one another as a means of cementing their social ties and hierarchies. Among the Kwakiutl, wealth only was socially significant if it was imbricated in an exchange, a promise to give at some point and receive at others. Viewing the potlatch as a simple feel-good gesture, as Boas and several of his colleagues did, underestimates the significance and specificity of what the Kwakiutl valued in the exchange of these goods. Offering these goods to others is not a way of recognizing other’s needs, but more importantly, a means of demonstrating one’s bounty, showing that the giver has nothing to lose by gifting or even destroying a good portion of their own wealth. Because elite families were the only ones who could host potlatches, they were obligated to give the greatest, including non-material things of value like titles and places of rank, especially to outsiders. The potlatch diminishes the significance of receiving, and instead affirmed the significance of giving.

I really like using the potlatch as a way of thinking about the limitations and possibilities of modern generosity and exchange, with regards to the particular gifting and receiving of food. Though there is no etymological relationship between the potlatch and the potluck (the latter comes from Middle English, and focuses on the notion of collective contributions to a shared table), it’s hard not to see the similarities between the two, and to imagine the significance of gifting as a means of affirming your capacity to have less than what you currently possess. It’s not an entirely selfless act, in that what you are showing is your own largess—but it is also a surprisingly anti-materialist act, a way of relinquishing goods in order to invite connection. During the first few months of the pandemic, we established an informal exchange with my mother and sister’s households, leaving bags of potatoes, jugs of olive oil, and enormous packages of toilet paper on each other’s doorsteps, an acknowledgment that we were all facing the same uncertainty and anxiety about running out of the essentials. Once we realized that toilet paper was not going to disappear from stores, we started sharing more interesting items—sourdough starter (a short-lived phase), fresh tomatoes, flats of peaches and blueberries from local farms. Suddenly what we were doing was not sharing resources out of mutual need, but out of mutual joy. I finally understood that old quote of Thornton Wilder’s about money: “It’s not worth a thing unless it’s spread around encouraging little things to grow.”

Why do moments of exchange only happen in moments of crisis or want? Could we bring back a shared economy of household goods and discoveries predicated on curiosity? Could knocking on a neighbor’s door actually facilitate friendship rather than suspicion? And could we use the model of the potlatch in other circles of exchange—perhaps in the marketplace of ideas? I’ve had robust conversations with librarian friends about the value of open access publishing, but I want to take the concept even further, to make public-facing, non-paywalled work a required component of advancement in the scholarly world. I want scholars to write more about how much they didn’t know before they knew, their long periods of ignorance and what helped them out of them, the major mistakes or misunderstandings they had that once sent them into humiliation spirals, that they can easily correct now for others. (I’ll share mine now: it’s pronounced Doo-BOYS, not Doo-BWAH. Now you’ve been saved several hours of self-flagellation that I’ll never get back again.)

It’s difficult to convince people who’ve fought tooth and nail for their positions to admit their failures (past, present, and ongoing), but the only way to dismantle a system predicated on silent struggle is to start speaking up about one’s learning process—acknowledging mistakes made and how you learned from them. I’d like to think of this as an intellectual potlatch—the ability to acknowledge one’s possession of power as having been acquired rather than innate, and the willingness to either destroy it or pass it on to others. It may not be as tasty as a cup of sugar, but I guarantee it is far more sustaining.

Recommendation: I’m wrapping some things up before I head to the UK next week for the Oxford Food Symposium (stay tuned for two photo-heavy newsletters to come!), but work permitting, I’m hoping to bring two pleasure reads with me, Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus (a supposedly lovely novel about science-oriented cooking in the 1960s—very relevant to my diss!) and a reread of Bob Gottlieb’s Avid Reader, a lovely testament to the work of editing and proof that reading enthusiastically and reading critically are the same thing, both requiring rapt attention and, perhaps most importantly, genuine good will towards the author. I’ve said enough about my experience with Gottlieb in a previous post, but I just wanted to drop in this one quote from his Paris Review feature (worth a read), “Whatever I look at, whatever I encounter, I want it to be good… I don’t want to interfere with it or control it, exactly—I want it to work, I want it to be happy, I want it to come out right. If I hadn’t gone into publishing, I might have been a psychoanalyst; I might have been, I think, a rabbi, if I’d been at all religious. My impulse to make things good, and to make good things better, is almost ungovernable. I suppose it’s lucky I found a wholesome outlet for it.” What a tremendously brilliant and generous mind he had, and how lucky we all were to benefit from the literature he sent our way.

The Perfect Bite: In between swimming sessions on Saturday morning, we decided to grab an early lunch at a little place in Waltham, Tap Tap Station Cafe, which specializes in Caribbean cuisine. It’s a pretty small menu (with almost no prices listed) and very few seats, but the food was freshly made and absolutely incredible. We opted for the daily special, the fritay, a Haiti-inspired platter of mixed fried items, including chunks of tassot (fried beef), accra (fish cakes), banan pez (also known as maduros), and a dish of pikliz (lightly pickled cabbage, carrots, and scotch bonnet peppers). We also got the jerk chicken with rice and beans and fried plantains, and the depth of flavor on the jerk (spicy, smoky, fall-off-the-bone tender) was amazing. I can’t wait to go back and try the rest of the menu, especially the griot.

Cooked & Consumed: We heated up the grill this Friday for some asparagus, portabellos, potatoes (par-boil first, makes all the difference!), and a new-to-me cut of steak, the picanha. Also referred to as a sirloin cap or culotte, it’s a Brazilian cut of steak that has a thick layer of fat on it that cooks up beautifully on the grill (like a delicious piece of pork belly). We seasoned it with salt and let it sit in the fridge during the day, then cooked it slowly over indirect heat on the grill. Absolutely amazing. (I picked this up at my favorite place to buy meat, Tendercrop Farm in Wenham. It’s the only “farm stand” I’ve ever been to with a substantial selection of its own hormone- and antibiotic-free pork, beef, and poultry, and the only place where I even bother to buy pork chops. If you’re even driving through the North Shore of Massachusetts, make sure to stop by (and bring a cooler bag with you).

I spent a large part of my childhood in a culture of reciprocity and sharing. A culture where community mattered and was strong. It also happened to be a culture and place of scarcity, which I'm certain was not coincidental.

Part of the problem with trying to evolve into a culture of sharing and community in the United States (with exceptions) is that Americans are so deeply, unabashedly, and unrepentantly (if that's not a word, it should be) individualistic. Centuries of that mindset are difficult, if not impossible, to reverse. The US is also a culture of plenty, whether that is true on the ground or not. As such, the proverbial lend me some sugar would no doubt raise eyebrows from neighbors who assume you can just go to the store and buy some for yourself, even if you need it RIGHT NOW.

That said, in an app like the one you propose people would opt into it so they would already be the kind of person for whom this would work. The trouble, I think, would be finding enough users near other users to actually make it work. I like the idea. My neighbors, of course, would have be cool with the fact that I'll be in my pajamas and have messy hair when they come get the sugar.