Non-Required Food Reading

A (completely biased) list of must-read texts in American Food History

When I started learning about food in an intentional way in the early 2000s, my curiosity was piqued mainly by two texts: Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation, a meticulous investigation into the ripple effects of the American fast food industry, and Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, a personal consideration of the impossibility of ethical eating in the less-than-transparent American food system. Both books are masterful pieces of public-facing journalism, and the first-person narrative in Pollan’s book in particular provided a genre-changing model for how to write (and read) about food. As time went on, however, I realized the books that would answer my broader questions about American food—how we came to like the foods we like; who has historically grown, sold, and cooked these foods; and the implications of our tastes on broader industries and communities across the country and globe—required a much bigger library.

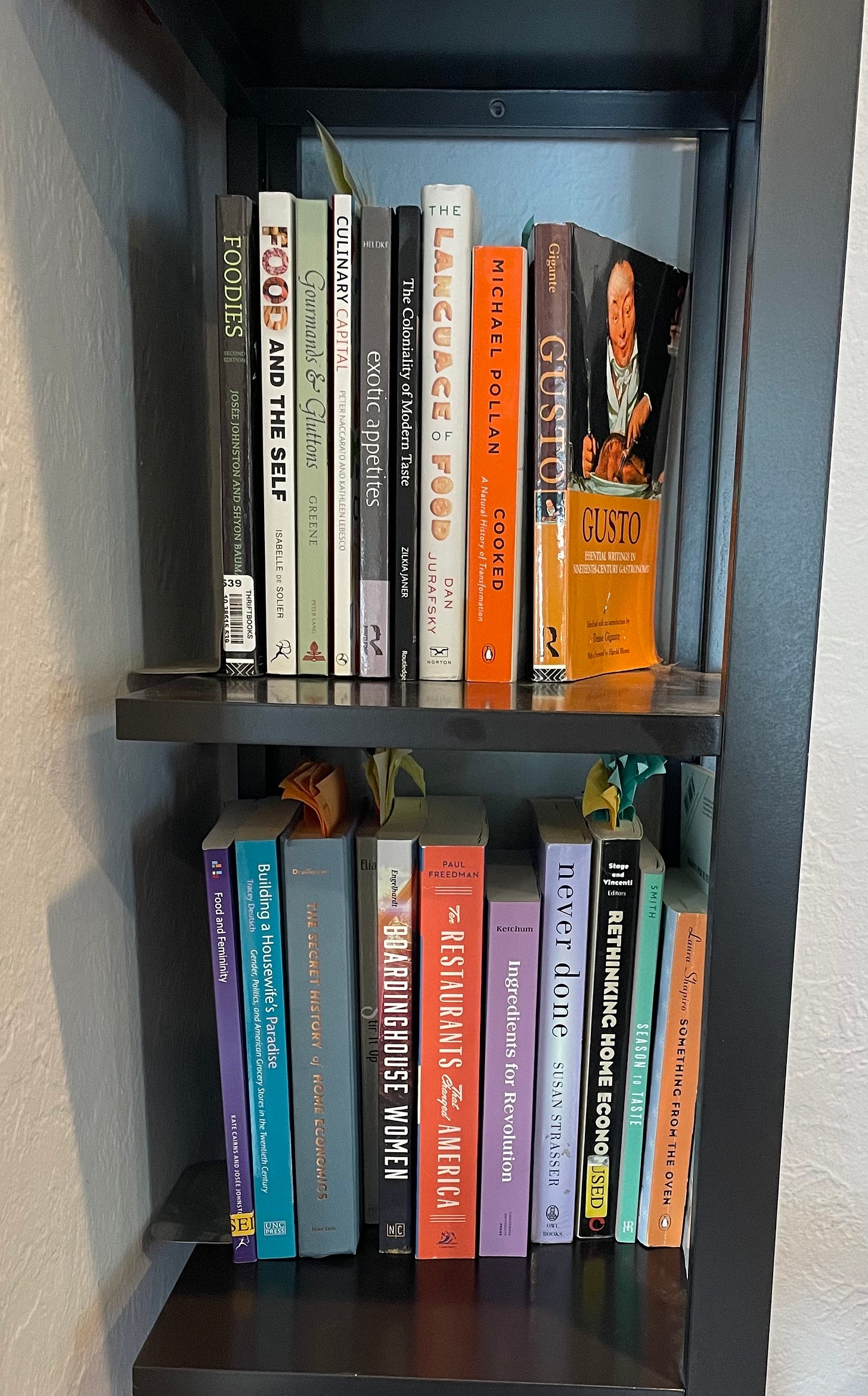

This week, I had to return countless volumes that informed my dissertation to the university library system, which means that essential books that have shaped my thinking over the last 6 years are no longer within my reach. At the same time, I’ve built a self-directed library that will hold me in good stead until I can rustle up enough freelance income to buy more titles (and bookshelves). I pulled all of my food studies books off the shelves, spread them out of the floor, and then started grouping them into various sections of reference. Some were easy to categorize—chronological, geographical, methodological—but others challenged me to think about each text’s pedagogical impact, how a book had pushed me beyond my personal interests to go into another field or headspace entirely. It also revealed what I’d failed to study, and the areas where I—and other researchers and publishers—still need to play catch-up.

You can’t reduce food studies to ten essential titles. As a fantastic series of events I co-organized with the Graduate Association of Food Studies revealed, food scholars make their homes in any number of academic departments and institutions, and as such the canon is more of a patchwork of perspectives rather than generated by a single discipline. As one of the leaders of the field of food studies, Marion Nestle, observed, any self-proclaimed “canon” functions best as a starting point for discussion. “Should such a list exist at all?” Nestle asks, and if so, “what criteria should be used for inclusion?” From my position, the best reading lists don’t come from academia alone; instead, they blend scholarly sources with menus, cookbooks, magazine pieces, and newspaper columns from across the last two centuries, giving us a chance to think about food from multiple positionalities. A mere ten authors doesn’t do justice to the field, or to the industry of food writing and media. So instead, I’m offering (very biased) ten categories, from which you can build your library of choice. (NOTE: if you’re not sure how much these categories matter to you, start with the excellent volume The Food History Reader, full of primary source documents that will get you going):

The books that changed everything: The books that made countless food scholars sit up and say, “Ah, this is what I want to study.” Most food scholars would cite Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power, a definitive volume of “commodity history,” using a single agricultural or commercial product to expose the interconnected of historical systems and actors. (Basically, Sidney Mintz walked so Mark Kurlansky could run…and that’s a complement to both Mintz and Kurlansky.) Add to this key nonfiction titles on food systems: Marion Nestle’s Food Politics, the aforementioned Schlosser and Pollan books, likely some major books on social, cultural, and environmental history (see categories #4 and #8 in particular), a theory-heavy but enlightening book by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing called The Mushroom at the End of the World, and what I’d argue are two new classics, Kyla Wazana Tompkins’ Racial Indigestion and Michael W. Twitty’s The Cooking Gene. But because this category is about what catalyzes a lifelong love of food writing, it’s very open to interpretation.

Canonical writers and cookbooks: As with all good food writing, this includes a handful of male authorities (often professionalized gastronomes), but is generally dominated by women writers. Here you can find titles from Laurie Colwin, Julia Child, Edna Lewis, M.F.K. Fisher, Betty Fussell, and Ruth Reichl, along with numerous essay collections from Clementine Paddleford, Nora Ephron, Gael Greene, Freda DeKnight, and Mimi Sheraton. (This should also include nineteenth-century entries from Catharine Beecher and Juliet Corson, as well as a sampling of some of the best authors of domestic advice in the period, from magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book, Harper’s Weekly, and Ladies’ Home Journal.) A copy of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste is essential (get the translation by M.F.K. Fisher), along with the compendium Gusto which samples a number of nineteenth-century texts on gastronomy (aka the study of food centered on the experience of eating and tasting).

Major overviews of 18th/19th/20th c. American food history: I can’t cover everything here, but the texts that have been most useful to me are the ones that anchor me in a combination of archival sources and accessible historical writing. For big overviews of nineteenth and twentieth century food culture, and the women who shaped it, you can’t beat the books by Laura Shapiro, including Perfection Salad and Something from the Oven. For books on the anxieties around nutrition and hygiene in nineteenth-century America, try Harvey Levenstein’s Fear of Food and Adam Shpritzen’s The Vegetarian Crusade. If you’re focused on American during wartime and the Great Depression, you’ll want a blend of the many great books by Jane Ziegelman and Andrew Coe, or if you’re taking a global scope, you can’t do better than E.M. Collingham’s Taste of War. You also need key texts that address what’s going on in the rest of the world that shapes American tastes and trade from the period of settler colonialism to the present, but that opens up a whole slew of texts that merit another post entirely…

Race, Ethnicity, and the Plurality of American Cuisine: One of the reasons I’m so proud to contribute to SAVEUR is that I think of the American food palate as built on the multi-faceted traditions and diasporic communities that call the United States home. It’s impossible to do justice to this in a few callouts, but the books that have earned a permanent place on my shelf include those by Adrian E. Miller, Donna Gabaccia, Hasia Diner, Krishnendu Ray, and Fabio Parasecoli, among many others. There is no such thing as a monolithic text on Black or immigrant cuisine in America, nor should there be—the point is to curate a list that speaks to and from the community you hope to study and understand, and should engage embedded research and primary sources from wherever a community lives. So for Black and Southern food history, books from Jessica B. Harris, Marcie Cohen Ferris, Judith A. Carney, plus a few issues of Bitter Southerner and Gravy, should always be on hand. If someone is studying diasporic foodways, you must consult the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota, far and away my favorite archive throughout my graduate years.

Environmental History/Studies: In the 1960s and 1970s, Americans came into a popular understanding about food culture at the same time that they were asking major questions about natural resources, agricultural policy, and environmental ethics. Both Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Aldo Leopold’s A Sand Country Almanac were key texts for the environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and they found counterparts in the works of Frances Moore Lappe (Diet for a Small Planet), Euell Gibbons (Stalking the Wild Asparagus), and Wendell Berry (The Unsettling of America). My favorite of this lot is a book that connects directly to food studies and its relationship to the “natural” or “wild”, William Cronon’s Changes in the Land (which I’ve been told developed from his undergraduate thesis at the University of Wisconsin-Madison—wow) and Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. Basically, if you want to think about food as linked to nature…get your hands on some Cronon, stat.

The counterculture and its scholarly descendents: If the concept of the American food “counterculture” throws you for a loop, start this journey with Warren Belasco’s definitive text, Appetite for Change, which should be accompanied by other volumes about the gourmet revolution in the same period by David Kamp and Jonathan Kaufmann’s Hippie Food. (Make sure you pair these with primary source docs from Alice Waters, J.I. Rodale, Anna Thomas, and the Moosewood Collective.)

Labor histories: If we’re going to talk about taste, we have to talk about labor, and the many hidden and under/uncompensated histories that make our food system run. A few shoutouts that have a permanent place in my library: Julie Guthman’s Agrarian Dreams, Sayu Jayaraman’s Behind the Kitchen Door, Moon-Ho Jung’s Coolies and Cane, and Seth Holmes’ Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies. Any conversation about the relationship between provisioning and the ethics of food should include Cultivating Food Justice, and engage with the ongoing research from Alison B. Alkon, Teresa Mares, Laura Minkoff-Zern, and more. But if there’s any major hole I’ve identified in food reportage and scholarship, it’s material that addresses the hidden labor force that makes the prepared foods that fill in the gap between what Claude Levi-Strauss called the “raw and the cooked,” the many paid but invisible laborers who create America’s pre-prepared foods. Amy Trubek’s Making Modern Meals is an important start to addressing this topic, but there’s still much work to be done.

Women’s work: There’s no escaping it—for the vast majority of human history, cooking has been women’s work. So a few key volumes on women’s history, and particular women’s (generally unrecognized, uncompensated) domestic labor are essential. Books by Ruth Schwartz Cowan, Susan Strasser, and Sherrie Inness are all vitally important to building a culinary library that brings women’s voices to the fore. Books that reflect specifically on the labor experiences of Black, Indigenous, and Asian women are essential to building a global feminist perspective, and I have several titles from authors including Jessica B. Harris, Devon Mihesuah, and Anita Mannur among those in my collection. Building a library that incorporates embedded, ethnographic research also means pushing into the kitchen itself, and there’s no books that do it better than Meredith Abarca’s Voices in the Kitchen and Rebecca May Johnson, Small Fires.

The meaning of food: There are a handful of theoretical texts I turn to on this topic again and again—Josee Johnston and Shyon Baumann’s Foodies, Peter Naccarato and Kathleen LeBesco’s Culinary Capital, and Isabelle de Solier’s Food and the Self—but honestly this category should include the many ways that the meaning of food defines easy sociological categorization.th vital and far-too-infrequently-expressed power. Add to this the new but excellent essay collection from Ruby Tandoh, All Consuming, and you’ve got a unique series of texts that deeply interrogate just why we care so much about the food we eat.

The books that speak most directly to what you care about: Is the science of cooking your focus? Then you likely need volumes from both Harold McGee and Sandor Katz. Do you want a deep dive into the American South? Then you’ll likely want to consult titles by David Shields, Marcie Cohen Ferris, and at least a few issues of The Bitter Southerner. If you’re an anthropologist or a sociologist, you will have key theorists and perspectives you need to engage with in order to prove your interest in food through the lens of your discipline. But at the end of the day, the question is: have you pushed yourself to think beyond your default mode of engaging with food? Whose experiences, knowledge, and perspective do you need to engage to move beyond the plate and into something deeper and more critically informed? Ultimately no reading list can speak perfectly to that; you take it forward from there.

Recommended Reading: In contrast to all of the above, I’ve been immensely enjoying my research towards a piece on food in crime fiction (much more on that to come). And of all the books I’ve read thus far, I’ve been hooked on John Lancaster’s The Debt to Pleasure, or what I’m starting to think of as the Pale Fire of the foodie set. I don’t want to give away any plot points, so I’ll just say that it’s so rich with food description (in gleanable recipes and in general description) that I wanted to underline and cook from every page.

The Perfect Bite: Last night we had some friends over for a long-overdue hotdish-fest, and great food was enjoyed by all. (My contribution: a very foodie-friendly but Midwesterner-approved casserole from Molly Yeh.) But our friends showed us up with dessert: a Snickers Salad, surely a dish concocted in a lab designed to enfeeble diabetics and gourmands alike. I’d never had anything like this, so I spent a solid five minutes trying to come up with an aesthetic assessment of what I was tasting. 24 hours later, I’m still not sure, but I’m still intrigued. There’s a post to come out of this for sure.

Cooked & Consumed: Giving a brief shoutout to my favorite non-pasta, non-rice pantry go-to: buckwheat soba noodles. Having been worn out by Saturday’s hotdish-a-thon, tonight’s dinner was simple yet satisfying: frozen soup dumplings cooked in a steamer basket, baby bok choy blanched and lightly drizzled in soy paste, and a package of soba noodles cooked and dressed with a ginger- and sesame-oil sauce. A healthy and satisfying meal cooked and on the table in less than 30 minutes; not too shabby.