Over the last few weeks, I’ve been prepping for two conferences, one at which I’ll lay out a 15-minute oral version of the introduction to my dissertation, and another where I’ll circulate a (significantly trimmed) version of an in-progress chapter. These processes have felt like the simultaneous weeding and filling of a garden: I begin digging in the dirt with a general impression of I want to grow, only to encounter weeds and vines as thick as my arm in the soil. I dig and dig to uncover the source of the plant getting in my way, only to find that I’m tapping into a larger network of unseen, flourishing impediments. Sometimes I can pull the gnarliest of the weeds with its roots intact, and reveal in my ability to thoroughly clean up a patch for planting, while at other times I find myself barreling ahead, using shears to chop through the vines without ever uncovering their source, all the while muttering to myself the plant version of the old adage, “The best dissertation is a done dissertation.”

If the academic Twitterverse is correct, research and writing are supposed to be torturous, solitary processes that often lead a scholar down a multitude of dead ends, bad drafts, and even worse premises. So much of the horror people recount about their scholarly experiences seems to be rooted in the isolation of the writing process: the difficulty of sitting, alone with a blank page, then a bad page, then finally, after much wrestling through one’s ideas, a bad—but complete—draft. My first draft of anything I write is almost always a series of stabs in the dark, often rife with incomplete sentences, incoherent ideas, and very inconsistent tenses. But it takes writing out of the corner of my eye to get through to that first draft, so that later, when I’m feeling brave enough to do so, I can look at it directly and see, for better or for worse, where the weeds are.

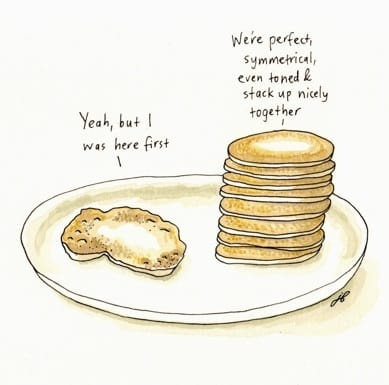

To a certain extent, I get a huge amount of pleasure of releasing that first draft into the world, even though I know that it is likely to be rife with faults and in need of a major overhaul, because it’s proof that I forced myself to do the work in the first place. It is a bit like the first pancake that comes off a frying pan—though it may not be as uniformly colored or cooked as the cakes that follow, I like the inconsistency and texture that it provides, the clear indications that the pan was hot and the butter was waiting for the batter. The adage that somehow the first pancake is always the one to throw out never made sense to me, in part because it was the one I always wanted to gobble up first—the one I was proudest to have cooked, and most eager to devour.

Why don’t we have more spaces for celebrating the first pancakes in our professional life—the bad ideas, the shitty sentences, the gazillions of citations that get incorporated then eventually thrown out once you figure out what you’re arguing? If we only expect things to be delivered in perfect form, how does anyone get over the pressure that comes with writing the first draft? I vastly prefer conferences that don’t require pre-circulated papers, as they can be places where one’s ideas have to be captivating but can still be a little underbaked, and where presentations are more like bulleted lists of potential trajectories than fully finished papers read aloud before a captive audience. Just as chefs often develop dishes as family meals or daily specials before they become menu staples, shouldn’t we have spaces to share our lopsided, lumpy ideas with an open caveat that they are still under construction? I’d like to believe that my career in food—a path that I’ve been carving out for the last two decades—leaves space for collaborating with others on ideas in progress. If we create spaces where we can all bring our “first pancakes” to the table, then surely it’s a much more rewarding feast for everyone…

Recommendation: I really loved this piece from Ifrah F. Ahmed in Eater, on her necessary and fruitful adaptation of Somali cuisine in the United States, and how she navigates accusations of veering too far from “authentic” expressions of Somali culinary traditions. My original graduate school proposal was to study the foodways of Somali and Hmong immigrants in the United States, and I found Soleil Ho’s concept of “assimilation food” an essential read, in that it details how diasporic cooking traditions are adapted not as a means of recreating the foods of one homeland, but as an opportunity to create a middle ground between the familiar and unknown, something distinct from “fusion” cuisine in that the mashup of foods is a means of cultural survival. Such foods are, as Ahmed notes, open to a degree of rebuke from within the diasporic community, and as a result, she found herself in Mogadishu in 2018 “having internalized the idea that the most correct Somali cuisine waited for me in Somalia, and that the global Somali diaspora could only offer a sliver of the real thing.” Yet as Ahmed says,

my time in Mogadishu helped me realize that we in the diaspora were actually the closest to the concept of “classic” Somali cuisine. Like many other immigrants and refugees, our cultural consciousness was frozen in the time that we or our parents left our homelands … That time before the war became a memorialized safe space, a nostalgic mental refuge to return to again and again.

The idea that Ahmed presents, that diasporic cooking may be “truer” than the rooted cooking she observed in Somalia, is a fascinating one to think through, where we can imagine cuisine as both a bridge to a homeland and a crutch or barrier from future innovation. Ahmed ends with a provocation about the nature of fusion, tradition, and “authentic” cuisine: “Are my anjero burritos ‘fusion’ food if I haven’t changed any of the original ingredients? I don’t believe so. Are they a classic Somali food widely known to everyone? Definitely not. Are they a traditional food? Maybe just to my family. But I do know one thing for sure: They are authentic to me.”

The Perfect Bite: Late last weekend I watched my 3yo eat her first-ever soup dumpling (xiao long bao), and boy, if there was ever a food that deserved the “perfect bite” framework, it’s this one. This deep dive at Afar into the history of the soup dumpling—from a teahouse staple outside of Shanghai, to a Taiwanese delicacy pitched to Japanese consumers, to a transplanted phenomenon in Los Angeles—really adds so much complexity and depth to the dumpling’s path to popularity. But it also made me think about what is being lost when soup dumplings can be cooked straight from the freezer in one’s home kitchen (as is becoming increasingly easy to do). When one eats xiao long bao for the first time, one usually has to be taught how to do so by an expert diner to avoid being scalded or splattered on first bite. Will the soup dumpling eaten at home, navigated outside of the social realm of the shared restaurant table, taste as good? I’m curious to see what others think here…

Cooked & Consumed: We’re finally in spring weather here in New England, which means I want to chop up fresh herbs and put them in everything. So while sharing dishes with some friends last night, I threw together this delicious salad from Love & Lemons, grabbing fistfuls of the various mints, basils, and alliums from my garden for the dressing. I finished the salad with flaky sea salt and my favorite stealth ingredient ever, chive blossoms, giving that tiny note of oniony freshness to the dish along with some little pops of pale purple color. If you spot them in a neighbor’s garden, make friends with them right away while the blossoms are abundant—the flowers will be gone before you know it.