Despite calls to make it a regular habit—for cost-effectiveness, for maximum quality of ingredients, for environmental impact—seasonal eating only really takes hold of the American diet around November, when every food magazine, digital resource, and online content mill goes into Thanksgiving overdrive. Though the pumpkin spice offerings and decorative gourds come out earlier and earlier each year, we don’t shift to the roots, hearty greens, and winter citrus until it comes time to assemble the Thanksgiving feast. Though there are a few things that always show up at our Thanksgiving—my mom is forever devoted to her turkey recipe, stuffed with Southern-style cornbread and cooked over a sauternes-soaked tub of dried peaches, apricots, pears, and shallots—what I’ve loved more and more is giving myself over to whatever the market has to offer, deliberately leaning towards bundles of swiss chard and kale and stepping away from the delicate peas and asparagus of summertime salads. If the central myth of the holiday is that of the Pilgrim commemoration of surviving their first year in the Plymouth settlement, then the harvest feast becomes a powerful symbol of indebtedness to the natural landscape. Both religious and social, it claims a status that is both reflective and performative.

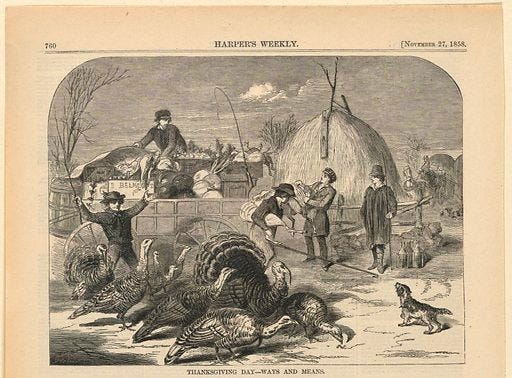

Even as food publications dedicate themselves to offering 25 new ways to prepare the worst member of the poultry family, historians are obliged to reckon with the emptiness of the Thanksgiving “myth,” and acknowledge everything that gets pushed under the table—the too-brief peace accords and promises broken, the landscapes destroyed, and that the only reason we have the rosy portrait of the Thanksgiving feast is because of those who demanded we tell the tale. Many of the central tenets of the Thanksgiving holiday are only as old as the nineteenth century, rooted in the commercialized unifying portraits by Sarah Josepha Hale, Caroline Howard King, and Harriet Beecher Stowe to create a unifying national holiday following the end of the Civil War. Perhaps this is why the dishes that prevail at the table—the turkey rather than the fowl, eels, and venison documented in Mourt’s Relation, and the promotion of pumpkin pie and cranberries over the pecans and sweet potatoes of the American South—cement the idea of Yankee cuisine as the core of the holiday. Gone is the idea of a specific landscape of providence, or an acknowledgment that co-existence is the best path to securing a peaceful future. Instead, the idea of national unity comes via the settler colonial cooption of the pumpkin pie—the dish that emerged from Wampanoag gardens is now reframed as the truest of American dishes.

The wave of exceptional food books by Indigenous authors released over the last decade brings us back to the central concept of thanksgiving feasts (lowercase and plural, as there were many of them) as a continual opportunity to be anchored to the land, to see it as a source of abundance that will only remain if we honor as much as we honor one another. In his cookbook, The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, chef Sean Sherman writes about Native food sovereignty—the right to define and maintain one’s own food and agricultural system—as a foundational element of the tribal experience prior to European contact. As Sherman notes, tribes

“cultivated crops, foraged wild foods, hunted, and fished as good stewards. They relied on complex trade, held feasting ceremonies, and harvested food in common sites…my ancestors’ work was guided by respect for the food they enjoyed. Nothing was ever wasted; every bit was put to use. This parked creativity as well as resilience and independence.”

Sherman’s perspective on self-determination through food looks like seems at odds with an annual celebration of Thanksgiving, yet he has also written fondly of his family’s holiday gatherings on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, enjoying Lakota dishes like wojape and recipes straight from The Betty Crocker Cookbook. Though Sherman acknowledges that much of the story that underpins the holiday now feels like the mythology of a false past, the central values that lie behind the feast, and in particular the preparation of the feast, still ring true: “togetherness, generosity, and gratitude,” and through food, a celebration of “the beauty of the present.”

This idea of consciously living in the present of the natural world carries over to the thoughts of the botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, in which she writes about longing to be part of her local ecosystem to be of greater use to the world. Yet she acknowledges that “this generosity is beyond my realm, as I am a mere heterotroph, a feeder on the carbon transmuted by others.”

In order to live, I must consume. That’s the way the world works, the exchange of a life for a life, the endless cycling between my body and the body of the world. Forced to choose, I must admit I actually like my heterotroph role. … So instead I live vicariously through the photosynthesis of others. I am not the vibrant leaves on the forest floor—I am the woman with the basket, and how I fill it is a question that matters.

Kimmerer’s framing of the quandary of necessary consumption versus ecological justice takes the central tenet of thanksgiving seriously. If we are alive, and thankful to be alive, how do we ensure that we can live in balance with the world for the coming year? If we rely on living resources to survive, how do we take only as much as we need? Kimmerer’s response is to take “only that which is given,” which in many ways sounds like a more spiritual framing of seasonal eating...which is perhaps exactly what it should be. In her new book Seed to Plate, Soil to Sky, the food historian Lois Ellen Frank writes about Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) as the foundation of her teachings at the Institute of American Indian Arts, calling TEK “the perpetuation of the wisdom of the ancestors … used for life-sustaining knowledge and ways of living in the world.” Marrying seasonal eating and sustainable agriculture lies at the heart of TEK and of many different Indigenous culinary traditions—eating in harmony with the cycles of nature, harvesting with an eye towards future plantings, and hunting and honoring animals at the same time. Seasonality is the throughline that connects how we live to how we eat and underscores every dish and every photograph in the canon of Indigenous cookbooks that have emerged over the last decade.

It’s not an impossibility in the twenty-first century to live with such intentionality—but the presence of mind to adjust one’s diet from season to season is still hard to come by unless you live by the yield of your garden. So Thanksgiving is one of the last places for us to do so…and perhaps it’s only right that when we cook and eat so intentionally each November, when we meticulously plan our meals down to the last crumb of pie crust, we’re not only putting traditional foods on our tables but also a more seasonally, sensorially, and socially conscious state of mind as well.

Recommendation: To be quite self-promotional, my recommendation this week is the big roundup I wrote for SAVEUR on the best cookbooks of the year (which truly was only a sliver of the titles we brainstormed and initially drafted up). I don’t have favorites here, but one of my 2024 goals is to make one bookmarked recipe every week to start sharing with all of you, especially as a way of pushing out some of the glorious titles we just didn’t get to via the Cookbook Club. Check it out!

The Perfect Bite: Happy to hand this one over to my friend Matt this week, who arranged my first ever raclette experience. Raclette is a Swiss specialty that, unlike its messier drunk cousin you know as fondue, allows a bit more restraint and personalization in the consumption of the dish. Each diner has the chance to prepare an individual pan of melted cheese until it’s just to your liking, then scraped over whatever fixings you have on hand. It paired beautifully with almost everything on the table (sundried tomatoes, iberico ham, sliced radishes), but I especially liked it draped over crispy leek pancakes and topped with a few cornichons.

Cooked & Consumed: It’s time to clear out the garden planters before the daily frosts set in, so on Wednesday I pulled up the last of our tarragon and made Nigella Lawson’s recipe for butterflied roast chicken, marinated in tons of tarragon and lemon zest and roasted over a big bed of sliced onions. Served up with crunchy Brussels sprouts and big hunks of rosemary focaccia, it was exactly what we needed to get through the week.