This post is a bit short on personal meditations, in part because I just got back from a weekend away (and because my students are owed their grades), but also because this post really benefits from as many visuals as possible. On Friday I paid a long-overdue trip to the extraordinary bookstore Rabelais in Biddeford, Maine. I know it’s cliche to say that that I was a “kid in a candy store,” but truly, as a food historian-in-training (and generalist food nerd), I could’ve stayed there for hours without hesitation. The owner, Don Lindgren, is an absolute legend in the culinary and antiquarian books community, and he generously let me bend his ear about the worlds of food books, food history, and culinary ephemera of all sorts.

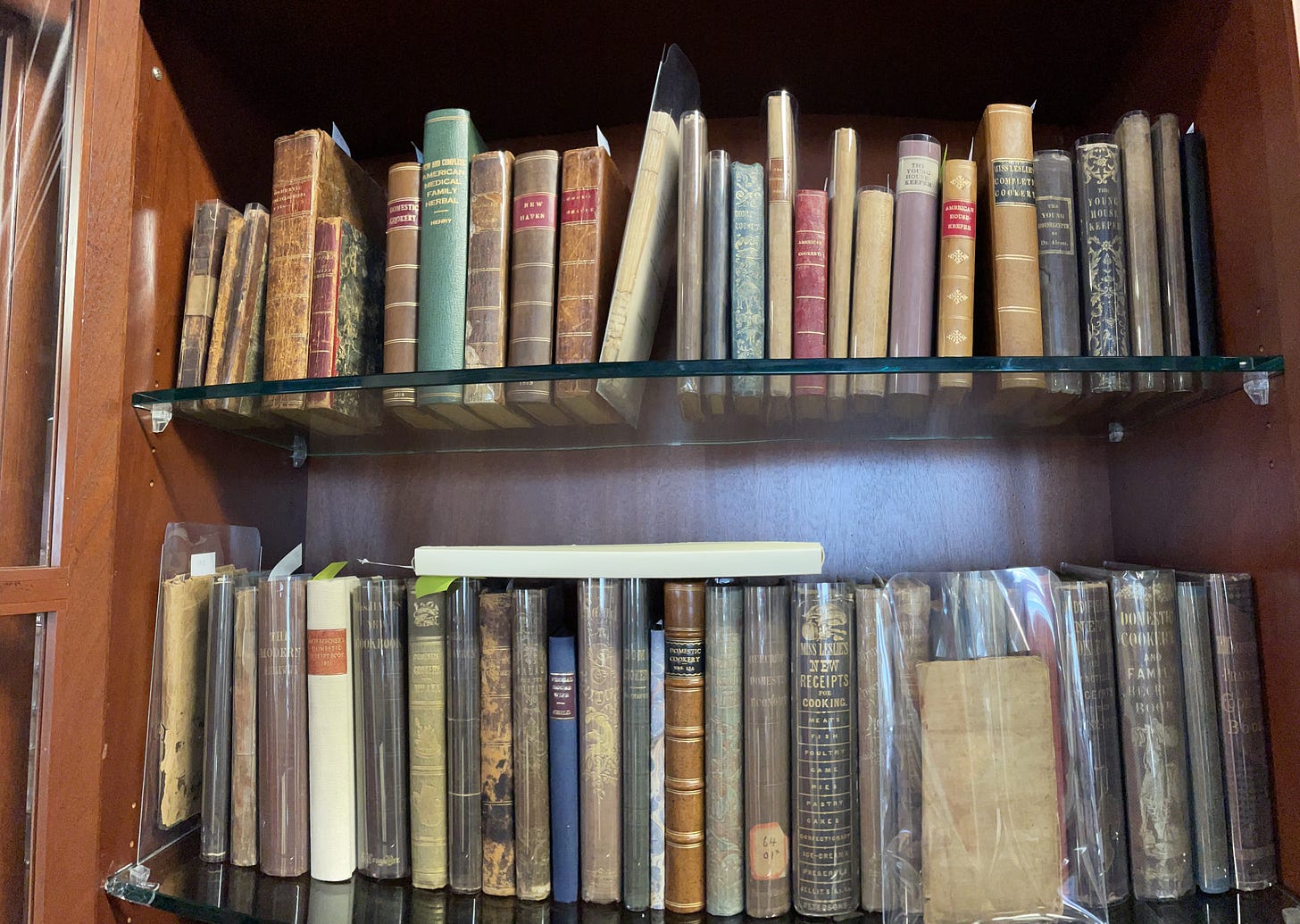

Lindgren noted that the pursuit of antiquarian books from across the evolution of culinary history gave him a tactile appreciation of the transformation of print technologies and the culinary cultures they sustained—the oldest books on this shelf of American and British cookbooks (dating back to the late eighteenth-early nineteenth century that I could see, though even older titles are in stock), emerged with wildly different binding and printing methods, at different trim sizes and with different degrees of textual details available to the purchaser. Books that belonged to personal collections of elite readers would be bound consistently with the same leather and paper selections to create uniform libraries, while other copies would be bound with giveaway leather and fabric from local butchers or tailors, or sometimes hand-glued/sewn by the individual who owned it.

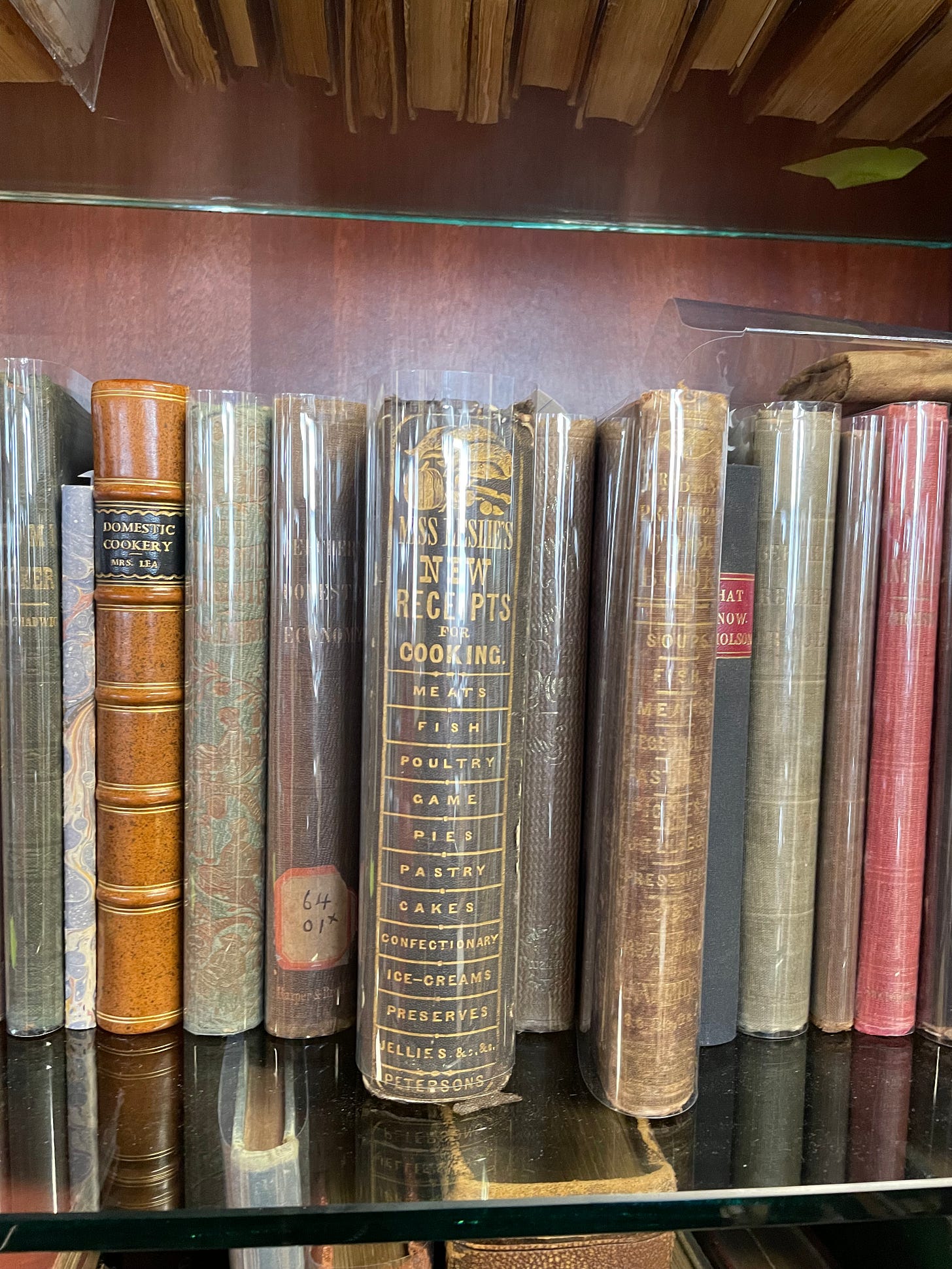

Yet as print culture around cookbooks took off in the mid-nineteenth century, the technology for commercial printing changed dramatically—books were not only more consistently standardized in terms of height and binding capacity, but also began to utilize their exteriors more intentionally to engage with the potential buyer. For example, this copy of Miss Leslie’s New Receipts for Cooking (1854) by Eliza Leslie was intended to be displayed spine-side out, a gilded table of contents for anyone to see.

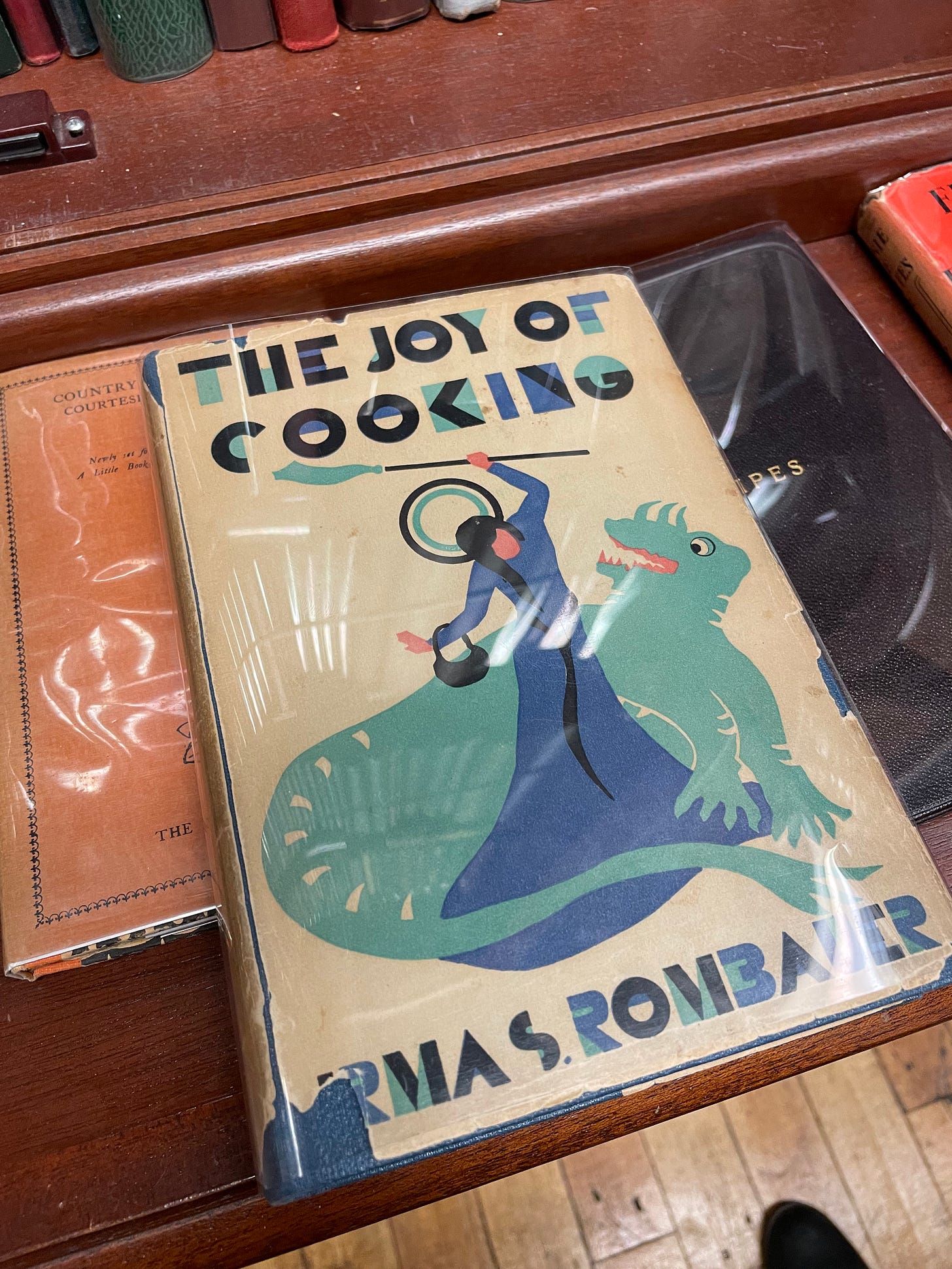

Dust jackets wouldn’t be utilized more extensively until well into the twentieth century, and even then, some titles arriving in Lindgren’s hands with the dust jackets intact can be extraordinary events. It is nearly impossible to find a copy of Irma Rombauer’s The Joy of Cooking in a first edition, which was privately published by Rombauer in an edition of 3,000 copies and illustrated and jacketed by Rombauer’s daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker. The jacket, according to Lindgren’s meticulous catalogue description, depicts “St. Martha of Bethany, the patron saint of cooking, who took up a mop to fend off the dragon Tarasque.” As my students discussed Rombauer’s text this week, and the backstory of the JoC’s inception (following her husband’s death by suicide in 1930, Rombauer published her longstanding collection of recipes as a means of self-sustenance, drawing upon her years as a homemaker and hostess in the St. Louis area), we debated whether the JoC would effectively be sustained as a text of impeccable taste and utility in the 21st century, or it, like so many Jell-O salads before it, might have fallen out of fashion. I can’t say for sure, but seeing the original jacket on the first edition gave me a newfound respect for it as a volume of enterprising culinary knowledge.

Here are just a few of the treasures he shared with me… (Note: descriptive text and captions set in italics beneath some images were written by Lindgren and his staff at Rabelais, with some purchasing details excised by me for brevity.)

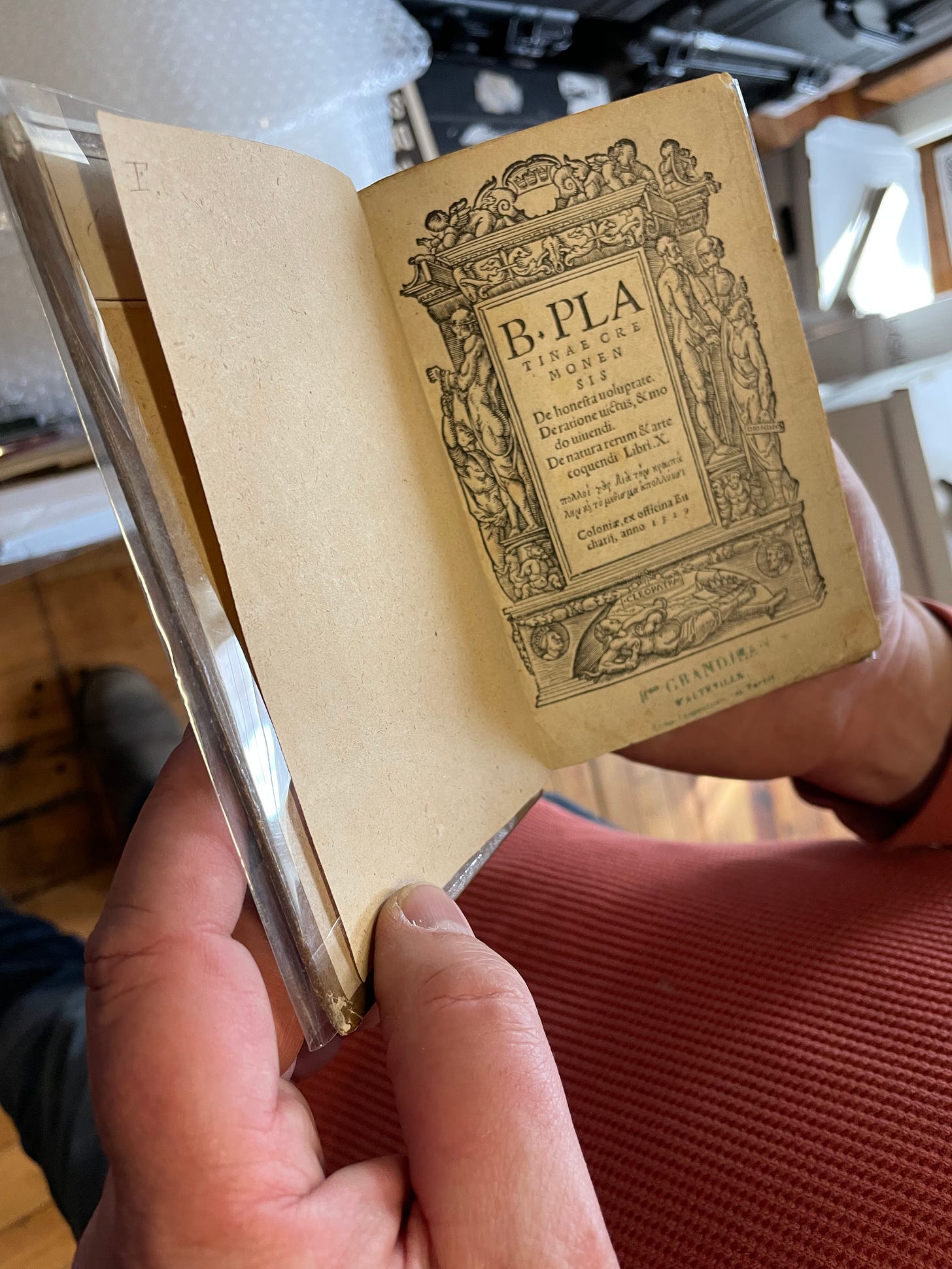

Printed in Koln by Gottfried Hittorp, an early 16th century edition of what is considered the first cookery book to be printed, first issued circa 1470. Platina (Bartolomeo Sacchi) examines the mode of living most beneficial to the human body, the pleasures of the table, and how to best enjoy one’s meals and have good health. He discourses upon the quality of various meats, fish, fruits and vegetables, the best manner to prepare them, and the correct sauces to be served with various dishes. An entire chapter on wine and vinegar is included as well.

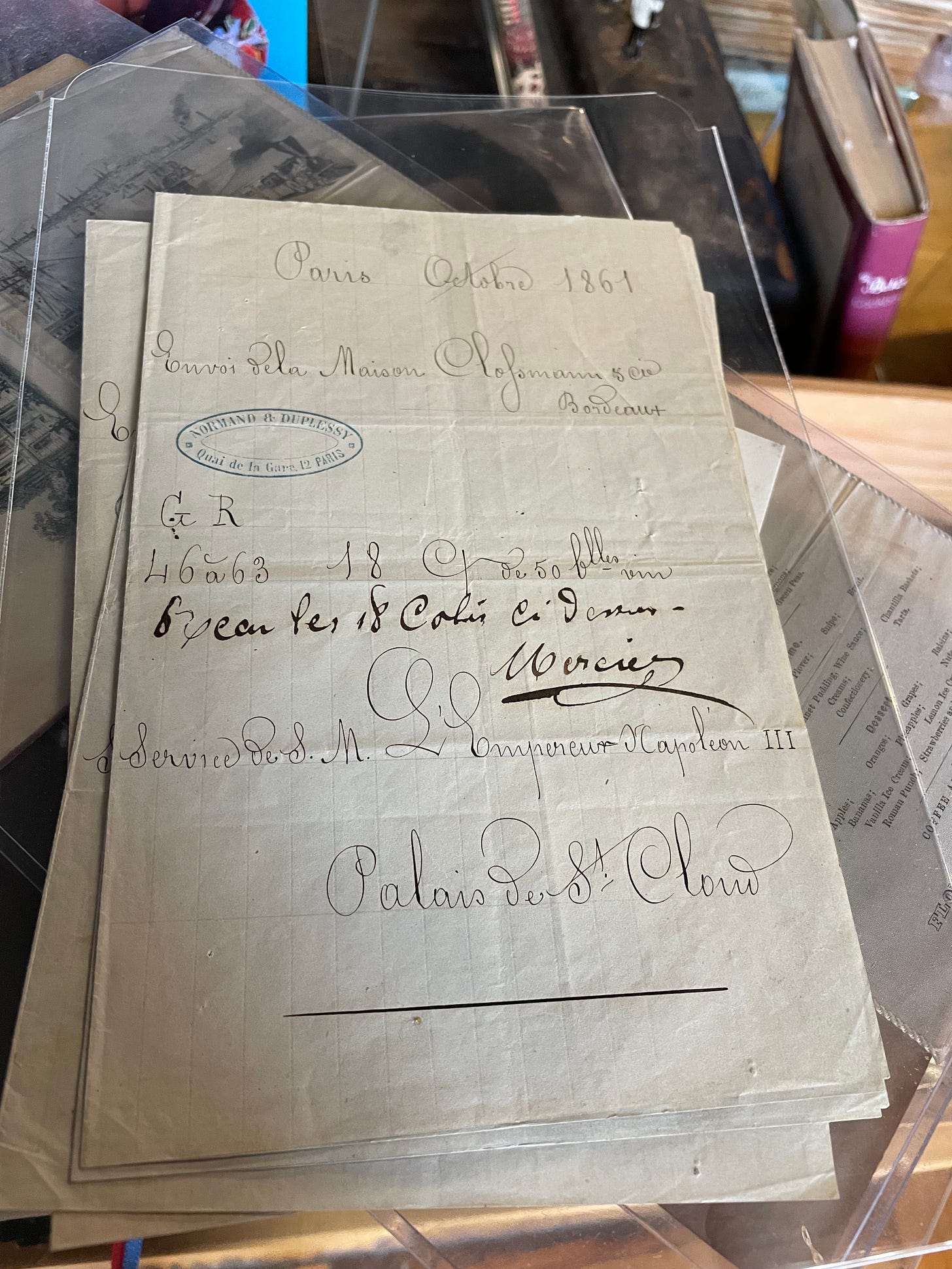

Receipts for four simultaneous purchases of wine from the Bordeaux wine merchant Maison Clossman, each for delivery to a different palace of Emperor Napoleon III: Palais des Tuileries, Palais de L’Elysée, Palais de St. Cloud, Palais de Fontainebleau. The items are numbered across the four invoices in consecutive order, with one hundred seven items in all, most large quantities in barrels or cartons of fifty bottles each. The fourth and final invoice contains an additional stamp in green ink, "Maison de [ill.], Service de la Regie de Palais de Fontainbleu".

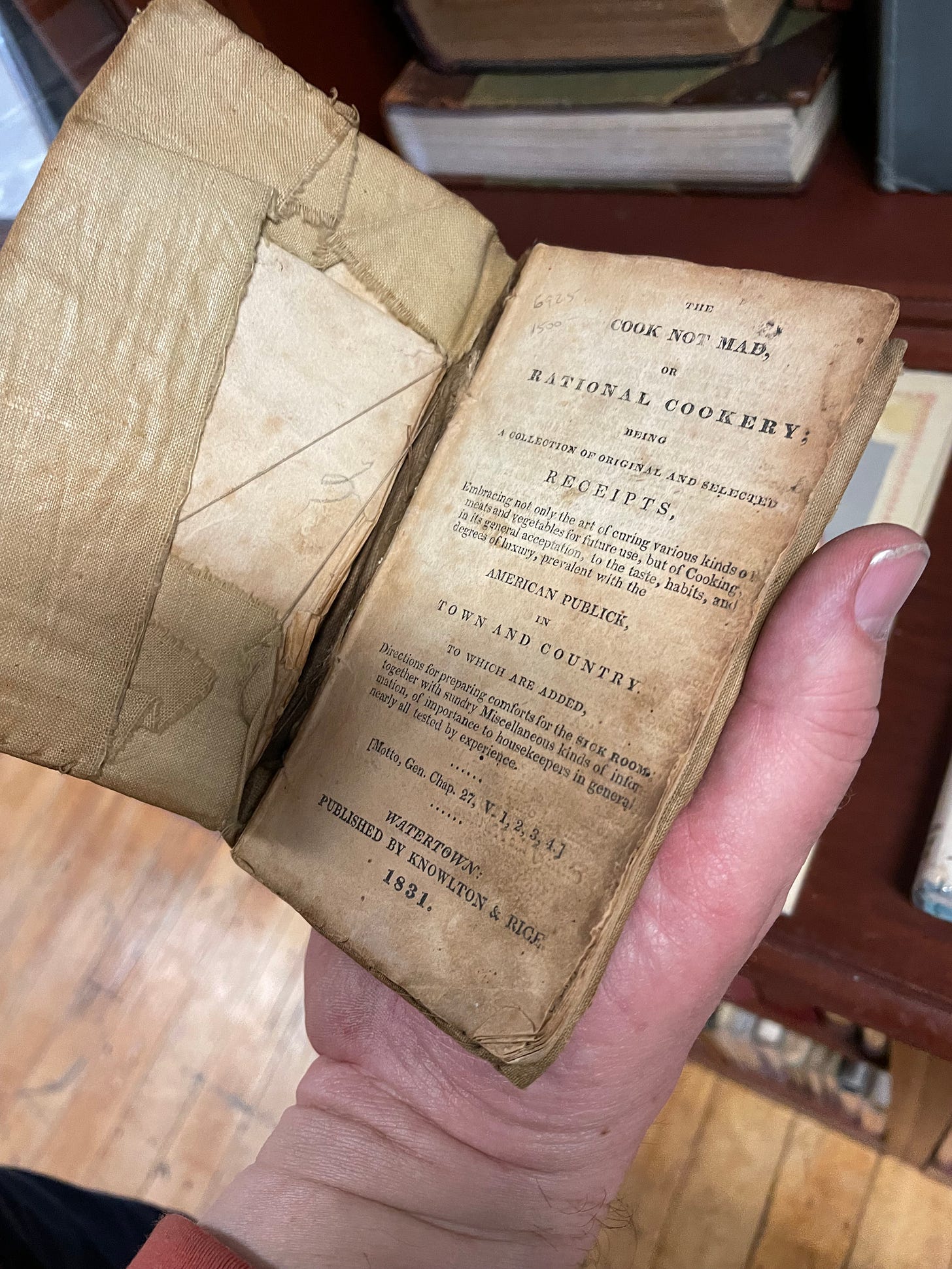

This book is clearly intended for the "American Publick" as it states in the introduction. Within you will find no “English, French and Italian methods of rendering things indigestible, which are of themselves innocent, or of distorting and disguising the most loathsome objects to render them sufferable to already vitiated tastes... These evils are attempted to be avoided. Good republican dishes and garnishing, proper to fill an every day bill of fare, from the condition of the poorest to the richest individual.”

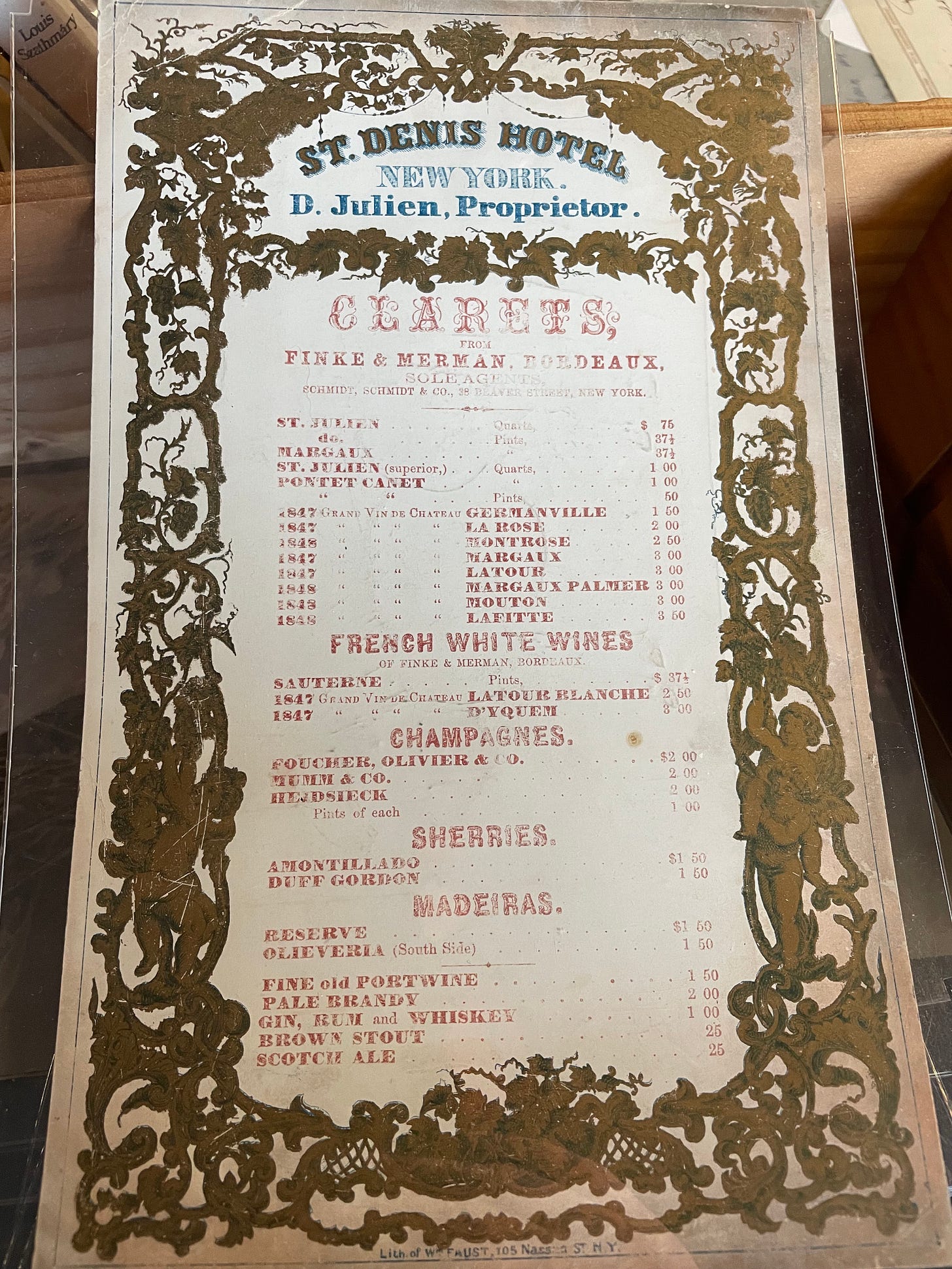

A very early wine list from an important New York hotel and dining establishment. ~~ Hotel at corner of Broadway and Eleventh Street, across from Grace Church and Rectory. Both the hotel and the church were designed by the architect James Renwick Jr. Named for its original owner, Denis Julien, the St. Denis Hotel opened in 1853, just in time for the Crystal Palace Exhibition. The building was leased to William Taylor in 1875, who incorporated the Taylor Saloon into the facility. ~~ An exceptional piece of chromolithographic printing, from a firm more known for fruit labels.

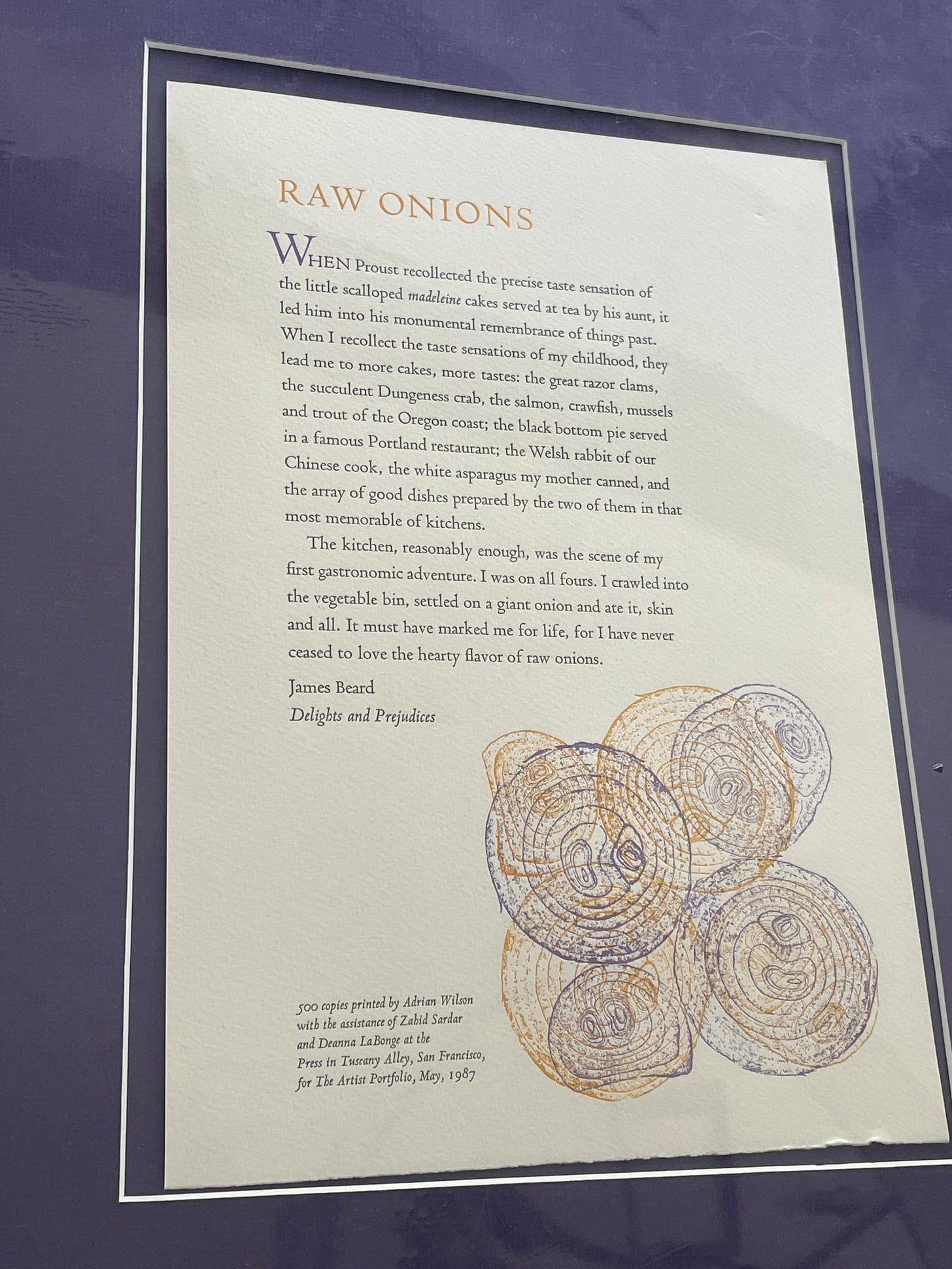

I could’ve stayed there forever, and I fully intend to go back, but I also knew that I wasn’t going to leave empty-handed. I bought myself a handful of treasures…first-edition copies of Craig Claiborne’s Kitchen Primer (1969) and Doris Muscatine’s A Cook’s Tour of San Francisco (1963), a copy of an April 1941 issue (issue #4) of Gourmet, and the one I’m most excited about, a print of “Raw Onions,” James Beard’s contribution to the Artists’ Portfolio, a fundraising project developed by a group of San Francisco-based restauranteurs and artists to support people fighting AIDS (following a benefit dinner/performance in June 1987).

Organized by Patricia Curtan and Will Powers, there were only 500 copies of the prints made—32 loose plates that included contributions from the chefs at Chez Panisse, Fog City Diner, and China Moon Cafe; culinary legends such as Marion Cunningham, Diana Kennedy, M.F.K. Fisher, and Richard Olney; and artists including Dvid Lance Goines, Jonathan Clark, Leigh McLellan, and Tracy Davis. My selection features the contribution from James Beard, which gains extra poignance given his position in the (less openly celebrated at the time) queer culinary community. It’s only fitting that the quote accompanying this print comes from his memoir, Delights and Prejudices, where he recalls one of his first “gastronomic adventures,” when he crawled into his childhood kitchen’s vegetable bin, scooped up a giant onion, “and ate it, skin and all. It must have marked me for life, for I have never ceased to love the hearty flavor of raw onions.”

I feel like I’ve brought more than a piece of culinary history home with me from my gastronomic adventure at Rabelais, and now I have to figure out how to give them all the pride of place they deserve. (Perhaps, for the Beard print, just adjacent to the onion basket in my pantry.)

Recommendation: If you haven’t guessed it, please get yourself over to Rabelais Books and buy some treasures yourself. But perhaps while you’re doing so, investigate your local restaurant supply store? I really loved Christina Morales' piece in the New York Times on how professional supply stores for restaurants have found a broader audience among home cooks, especially those who are interested in good workhorse kitchens that need to run well and cook a lot. I really adored going to supply stores when I still lived in NYC, and I need to get back in the habit.

The Perfect Bite: Is there anything as good as a griddled muffin? On one of our many diner visits this weekend, I got a chance to revisit my favorite breakfast item, a giant muffin that is split top to bottom, cut sides are slathered in butter, and slapped on a hot griddle until the cut sides are crunchy and warm all over. We were in Maine, so we went with blueberry muffins (even out of season, still sublime), but this technique is really an upgrade no matter what type of muffin you choose.

Cooked & Consumed: On Tuesday, I supervised an 18-person testing session of the recipes generated by my Writing Cookbooks students. They showed tremendous versatility in taking on each other’s recipes (and equally tremendous restraint in not rushing over to correct one another!), and I’m so proud of them for the valuable feedback they generated on each other’s projects. For logistical purposes I did test one recipe at home, a terrific take on the Mumbai street food pav bhaji, and it really makes me want to foreground the Indian elements of my pantry for more regular rotations, especially to better appreciate the many regional dishes I haven’t had a chance to try my hand at preparing. (Though I have to admit, all the students’ recipes were delicious upon tasting, and I was not at all unhappy to go home with leftovers!)

Sounds like the first of many trips to Maine! Love sharing your love of all things culinary.

Thanks so much for your visit! It was a pleasure to have someone here who can see what the shop has to offer.