The Way of the Future

Our Products and Our Perfect Selves

As a historian and as food writer, it’s fun to imagine my home kitchen as part of a time capsule. There might be one or two things that would date me as a food lover who came into adulthood in the early 2000s. Though I stocked my first kitchen with the standard college graduate package from Ikea, I slowly worked to replace each item with more professional-grade tools that mirrored what I saw my authors (and culinary idols) using. I bought my first chef’s knife at the end of my first restaurant stage, then lusted after a tower of Le Creuset pots I spotted in an author’s home kitchen, then picked up a cast-iron skillet after working on a book about fried chicken. Within my limited price range, I prized durability and versatility over convenience—I never bought an InstaPot or a slow cooker (though I was gifted one by authors for testing their recipes), and the most niche appliance I owned at the time was a rice cooker. (When it finally broke, I didn’t bother replacing it.) Though I’ve owned my home for the last three years, I’ve had little to no temptation to upgrade our big-ticket appliances. I like living at the intersection of practical home cooking and ambitious foodie aspirations—a microwave, sure, but a sous-vide cooker, absolutely not.

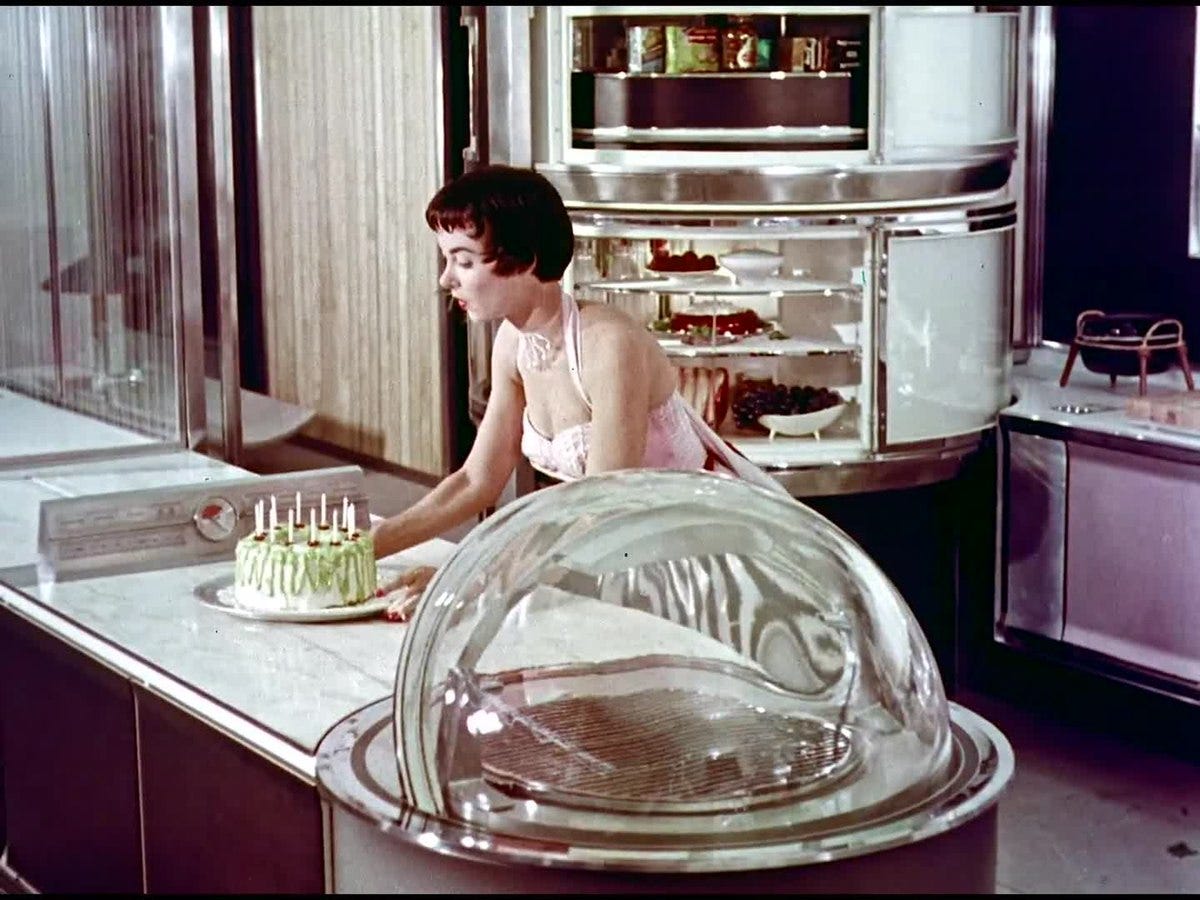

And yet kitchen goods are constantly being sold to us as a way of living out of our own time and skill set—a chance to live with the working materials of the past, or more often, the future. In the 1950s, Frigidaire (then a subsidiary of General Motors) sold its clientele on the idea of the “kitchen of the future”, a space where women could have technology custom-fitted to their bodies, and the promotions suggested, their lifestyles. Frigidaire’s film, “Design for Dreaming,” showcased a woman setting her cake batter to bake in a futuristic domed oven, then jetting off to the tennis court, golf course, and swimming pool, “free to have fun around the clock.” She then returns home (dressed once more in her full-length skirt and full face of makeup) to find her cake baked, frosted, and set with candles. The promise, it seemed, was to let women be as “free” as they wanted to be within the strict gender confines of mid-20th-century domesticity—but only modern appliances would enable that freedom.

There’s something delightfully quaint about the limited fantasies of futuristic living—technologically advanced, but conceptually retrograde. You can see these aspirations in all kinds of appliances and products from the 1950s and 60s—in the candy-colored kitchens supplied via the Frigidaire film and Westinghouse’s “all-electric house”, the streamlined silhouettes of American women’s fashion, even the omnipresence of red lipstick on American women—that served to support women even as they affirmed the importance of separate spheres and conventional domestic lives. It’s no coincidence that the home of Samantha Stephens, played by Elizabeth Montgomery on the 1960s show Bewitched, featured an iconic Frigidaire Flair stove, an appliance straight out of the Jet Age with its cantilevered glass doors, avocado-green siding, and its disappearing electric cooktop. Even a woman with magic powers still needed a little help from technology in the kitchen. Such an investment in contemporary technology also indicated a broader adherence to Cold War thinking: that science and innovation were not only valuable tools in winning the war against Communism, but essential ingredients in facilitating the comforts of American life. As Vice President President Richard Nixon argued to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in their famed 1959 “kitchen debate”, the ability to lighten the labors of American women through advanced household appliances was proof of the American desire for all citizens to live well in their own homes. “Your capitalistic attitudes,” Khruschev responded, “does not occur under communism.” Many historians have interpreted this comment as a retort showing the Western ideological trappings of domesticity, a chrome-adored cage in which women were told they should find personal satisfaction.

If the 1950s sold a version of futuristic femininity to draw women back to the kitchen, how then do the homespun aesthetics of contemporary kitchens do the same thing? How brands using the language of coziness and heirloom craftsmanship reframe the home as a site of genuine meaning-making and productivity—making it less like a laboratory and more like a workshop? What does the aspiration for hand-made pottery, vintage appliances, and slow-cooking technology say about our desire to look towards the past for models of living? The historian Rachel Laudan argues that seeking out stone-ground flour and heirloom vegetables has become more than an aesthetic preference, but a “moral and political crusade,” one that carries with it a rejection of anything that reeks of modern convenience or technology as “unreal”, in contrast to the old foodways as constituting the unimpeachable “real.”

Looking to what we buy and how we stock our kitchen as a way of accessing our truest, freest selves is almost always a fallacy. And yet we fall for it again and again, the promise of the One Pan to defeat all other pans, The Salt to season our meals to perfection, that single perfectly designed product to get to the best way of living. We invest things with meaning because they sell themselves as having meaning, as being solutions to the challenges of our lives. I’m as susceptible as anyone to the idea of being just one purchase away from total and complete capability towards any task at hand. But when I find myself reaching out towards the beautiful, retro, impossibly-expensive toaster, I have to ask myself exactly what level of capacity I’m hoping for—and towards what end.

Recommendation: Some of the thoughts in this post were inspired by a post by Kathryn Jezer-Morton at The Cut on the emergent #tradwife trend on social media, and what exactly it portends, politically and culturally. I was intrigued by how Jezer-Morton interprets the seemingly innocuous acts of domestic life—kneading sourdough, gathering flours, mending clothes—as revealing the inherent privilege of its practitioners, and (with more troublingly undertones) supporting an ideology that inherently endorses the conservative and often nationalistic underpinnings of such behavior. It’s a master class example of investigative journalism in questioning how we engage with “aspirational” social media content.

The Perfect Bite: At my mother’s Rosh Hashanah dinner this year, I was delighted to discover that she had made not just one, but two recipes from Shabbat, the latest book by Adeena Sussman. (Disclosure: I worked with Adeena on two cookbooks in the past, so I’m very biased in believing that she’s one of the great cookbook writers working today.) Both recipes were winners, but it was her vegetable kugel, full of latke-like shreds of potatoes, squash, and carrots, that was my absolute favorite. Once again, Adeena knocked it out of the park.

Cooked & Consumed: While recipe testing a delicious mole-like stew this week (more to come on that when it runs), I made a batch of white rice, albeit with some degree of trepidation, as I almost never made a pot of rice without unintentionally having the whole thing waterlogged or burnt socarrat-style. (As I noted above, my trusted rice cooker has long since gone to the Graveyard of Appliances Past.) So I was beyond delighted to discover that this recipe from Bon Appétit for the Perfect Pot of Rice actually yielded just that—a perfectly fluffy, well-seasoned pot of rice that didn’t stick even the tiniest bit. I was overjoyed that the promise of “perfect,” for once, actually delivered.

I have found for perfect rice a heavy bottom pan such as La Creuset is a must. And after washing I coat the rice with a bit of olive oil and quickly sauté. Then I cover with water and bring to a boil before covering. Enjoying your essays ❤️