Schmaltz for the Season

On the distinctly American story of Hanukkah, and the role of commerce in our holiday celebrations

My apologies for the misfired publication earlier (that went only to paid subscribers!) After contemplating through last week’s post, I’ve decided that while I’ll offer the option of paid subscriptions to those who want to become broader supporters/patrons of this work, I don’t have any plans to paywall any content—everyone gets to read, no matter whether they subscribe, and I’m going to honor that for as long as it remains feasible. Thank you for your support and continued readership!

To be honest, it’s never been clear to me how best to celebrate Hanukkah. If going by the liturgy, it’s a fairly minor holiday, chronicling the military resistance of the Maccabeus (Maccabee) family against the Seleucid king Antiochius IV Epiphanes in 168 BCE and the subsequent rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, lit by a insufficient amount of oil that miraculously lasted for eight nights. It isn’t chronicled in the Old Testament (only in the deuterocanonical books added by scholars, specifically Maccabees 1 and 2, and in the texts of the Mishna and the Talmud, written 600 years after the events they chronicle), and pales in religious significance next to Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur. It’s essentially a story about anti-assimilation, as the Maccabees were revolting against a king who demanded that they give up their public forms of religious observance (which included, natch, the consumption of non-kosher foods as a display of their submission). Defending one’s right to exist openly and free of persecution is definitely a narrative worthy of celebration, but it lacks the the expansive storytelling and menu of my favorite holiday, Passover. Apart from the latkes and the lights (that temple oil rearing its symbolic head), it’s a pretty laid-back affair.

Yet when practiced in the United States, one might think that Hanukkah was the most important holiday of the year. Much of Hanukkah’s significance as a holiday came about in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, during the peak period of Jewish immigration to the United States. In Europe and the Middle East at this time, many Jews celebrated Hanukkah, but did so in a fairly private fashion, and on varying dates from community to community (just as was the case with Thanksgiving). But from 1881 to 1924, 2.3 million Jewish immigrants entered the United States, spurred by pogroms, threat of military conscription, outright expulsion from their homes, and widespread displacement, and in finding themselves in a new country, forged a sense of shared community and identity wherever they met. They congregated together in settlements and tenements on New York’s Lower East Side, Chicago’s West Side, Boston’s North End, and in South Philadelphia, and became the foundation of new American industries such as garment workers (the rag-makers that fueled the ragtime of the twentieth century) and street vending. As the great historian Hasia Diner put it in her book, Roads Taken, “the act of peddling erased linguistic, national, and religious differences as barriers to social integration”, and created a mechanism by which Jewish merchants were integral parts of the American communities they intended to call home.

Commerce, it seems, has always been an effective way to leverage a claim to inclusion, especially in the late nineteenth century United States. Hanukkah owes much of its present-day significance to a single rabbi from Cincinnati, who hoped to present the minor celebration as an equal contender to the Christmas holiday. In the 1870s, the Cincinnati-based rabbi Max Lilienthal began to develop special celebrations for the Jewish children in his community, writing that they deserved “a grand and glorious Chanukah festival nicer than any Christmas pageant.” In late-nineteenth century America, Christmas was hard to avoid regardless of one’s devotional status—in 1870, it was officially made a federal holiday, in a move that many attributed to a desire for cultural cohesion following the end of the Civil War. (Again, there are more than a few parallels with how Thanksgiving gained national significance.) Hanukkah, meanwhile, had a much more grassroots campaign behind it, and the holiday was used as a rallying cry for the value of reform Judaism. That argument was furthered by the efforts of Rabbi Lilienthal and his friend Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who felt their adjustments could help Judaism survive as a religious and cultural practice into the twentieth century. Lilienthal even told his congregations that the Maccabees began their rebellion with the battle cry, “give me liberty or give me death,” the same challenge used by Patrick Henry to organize Virginia’s defense agains the British in 1775.

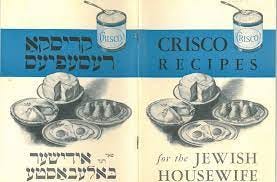

The best reason to align Hanukkah with Christmas was a commercial one—for by the 1890s, the leading department stores in the United States (Macy’s, Bloomingdales, and Sears-Roebuck) were all owned by Jewish families (, and stood to gain just as much from the holiday retail season if they expanded their marketing to both Christian and Jewish clientele. Christmas was no longer exclusively a religious celebration by this time, as annual celebrations, gifts, and cards had been popular since the 1870s. But Hanukkah required its own retail boost, and though all holiday marketing took a backseat during the World War I era, Hanukkah promotions were fully revived by the 1920s. Yiddish newspapers of the era carried advertisements for Hanukkah gifts, consumers could look forward to a wide range of branded food products, and numerous advertisers promoted their wares with the push for lekavod Chanukah (“in honor of Hanukkah”). Crisco, a vegetable shortening invented in 1911, found broad acceptance among the consumers who required a pareve frying fat to meet their seasonal needs. As a promotional Crisco cookbook published in 1913 declared, “the Hebrew Race had been waiting 4,000 years for Crisco.” For Crisco, profits had no religious marker on them, and as we’ve learned with the recent branding of Juneteenth, almost any holiday that can be rebranded as a special sales opportunity can be promoted to a position of major national significance.

This all begs the question: what would Hanukkah celebrations look like without their American consumerist rebranding? Is it possible to remember the specific story of Hanukkah even as it is promoted on a semi-equal status with Christmas? Perhaps the inherent problem of the American holiday season is that it tries to treat all celebrations as the same, shoehorning all religious and secular histories into the same buying patterns without consideration of their individual meanings and messages. Prhaps it’s much easier to celebrate a “holiday season” if it lives almost exclusively in the realm of commerce rather than in spiritual or religious worship—shopping doesn’t often demand nearly as much of us when it comes to self-reflection. Though Hanukkah may have been mainstreamed to the point of having its own wrapping paper, greeting cards, and endcap displays, it hardly offers a true route to religious or cultural inclusivity. Yet I’ve come to be contented with the concession that it reflects, the possibility that, all holidays being equal on the retail end, it is possible to have a few brief moments of intentional pluralism each year. So for the moment, I’ll have to take Hanukkah as it is, and be consoled by one irrefutable truth: that all the greatest Christmas songs were written by Jewish songwriters.)

Recommendation: It’s difficult to do justice to this topic via a single link, but I’d rather delegate it to writers far more intelligent than myself, and to whom my own thinking is hugely indebted. I strongly recommend you take twenty minutes to read Masha Gessen’s piece in the New Yorker on the politics of memory and how it clarifies—or clouds—our ability to understand the ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict. It’s both a clarifying reflection on the current moment and a resonant piece on the role that public history and public memory play in how we interpret current events.

The Perfect Bite: Is it strange if the best thing I made all week was a platter of wings? Well it was, if only because it gave me free rein to finally break open my holiday gift to my husband, the full tasting kit for this year’s Hot Ones Challenge. We are both extremely proud of our heat tolerance (having passed the progressively spicier tasting menu at Rhong-Tiam years ago with flying colors), and so on Wednesday we roasted up a platter of chicken wings and opened up the kit. Not only were there some genuinely delicious (and yes, spicy) hot sauces in this kit, but it was the most fun I’ve had tasting something in ages. Even my 4yo wanted to jump in on the experiment, and surprisingly loved the shishito pepper and garlic blend. Absolutely would recommend, even if your sinuses will be screaming at you later.

Cooked & Consumed: My favorite latke recipe comes via a song I learned in the junior choir at my synagogue growing up, which I rehearsed so many times it embedded itself in my subconscious. It’s an absolutely foolproof route to 15-20 perfect latkes, especially if you take two precautions: 1) be sure to squeeze as much liquid out of the grated potatoes and onions as possible (there will be a LOT of it) before mixing in the flour and egg, and 2) not overcrowd the pan when frying. The result is crispy, delicate, totally addictive latkes that will disappear in an instant.